5 Biographies Every Entrepreneur Should Read

- Patricia Curty

- Nov 13, 2020

- 8 min read

Updated: Nov 21, 2020

During his twenty-year residency at IBM, Thomas J. Watson Jr. pushed the organization ahead on a few fronts, including the progress from mechanical to electronic calculation.

All through A Business and Its Beliefs, Watson utilizes IBM as a contextual investigation. He clarifies that his dad learned humanistic administration as a youthful sales rep at the National Cash Register Company, one of the main deals driven organizations to zero in on the workers, under the initiative of John Patterson. For instance, Watson Sr. founded an open entryway strategy that offered the individual representative plan of action if his chief was being unreasonable. Many representatives would go to the corporate base camp on their vacation day to chat with the senior Watson about working environment issues. This associated the senior administration to the shop floor. Subsequently, Watson Jr. was made mindful of the disparity among hourly and salaried representatives' compensation, and, in 1958, IBM put everyone on pay to take out that unjustifiable practice. In the book, Watson Jr. compares representatives to Kierkegaard's wild ducks, each free and individual, flying as people, however in a gathering to one objective.

From 1914 to the furthest limit of World War II, IBM experienced quickened development and the authority at IBM needed to settle on choices dependent on sense as opposed to understanding, logical investigation. The achievement of these snappy choices was an immediate consequence of the directing hand offered by the association's solid conviction framework. As the organization kept on developing, IBM's center directors were, essentially, new to the organization, so IBM made two administration schools, one for junior heads and one for line administrators, to show IBM's standpoint and convictions to new workers.

In 1899, when GM was still headed by W. A. Durant, Sloan was the president of Hyatt Roller Bearing Company, a supplier to the nascent automobile industry. GM bought Hyatt in 1916, along with many of its other suppliers, and created a group called United Motors. Sloan was made a vice president and given some significant duties. He was also promoted to GM’s board. After World War I, the auto industry faced a significant downturn, and shareholders became concerned.

While Durant was regarded as a great visionary when it came to acquisitions and the automotive industry, he was not considered an effective manager.

Around this same time, Sloan became head of United Motors and wrote an organization study “as a possible solution for the specific problems created by the expansion of the corporation after World War I” and submitted it to the executive committee.

This study is one of the most important business documents ever written, primarily because, in those pages, Sloan revealed an organization that was so efficient, employing such processes as centralized buying and using interchangeable parts to build different GM cars, that they would ensure critical savings for GM at that time of struggle.

Sloan succeeded Durant as president in 1922 and later became chairman of the board in 1937. He proved during his time at GM to be one of the management masters of the twentieth century.

Richard Branson is arguably the most successful entrepreneur of the past half-century, creating 360 different companies and brands, from Virgin Cola to Virgin Music to Virgin Atlantic. Some failed, like Virgin Cola, and some set the industry standard, like Virgin Atlantic. But don’t think that Branson is done: he calls this book Volume One of his autobiographies. It covers the first forty-three years of his life, though the first chapter begins with one of his around-the-world balloon flights that failed in 1997. The book ends in 1993, when he was forced to sell Virgin Music to save Virgin Atlantic—a move he refers to as the low point of his business life. The overall theme of the book is survival, and this book is chock full of survival stories about his life, his remarkable entrepreneurial spirit, and his successes and his failures, which offer both inspiration and caution to those who would like to follow in his footsteps.

As with most autobiographies, we begin at the beginning, and Branson recounts his childhood, telling tales about family and school. Faced with the challenges of dyslexia and a rebellious spirit, Branson had an extremely hard time with authority at school. He had ideas about reforming some of the more arcane rules, and out of this desire came the student/youth newspaper called the Student that he started with his friend, Nik Powell (who would be a cohort of Branson’s throughout, enabling Branson to explore new ideas while Nik made them work on the front lines). The first issue was published in January 1968 when Branson was seventeen. Branson retells stories about how he and Nik called banks and large companies to get advertisers, and his methods reveal his ingeniousness. The pair called Coca-Cola, saying Pepsi was in the paper, and then reversed the tactic when calling Pepsi. Also he was fearless in pursuing the big story, and his interviews included subjects like Mick Jagger and John Lennon. Lennon almost put Branson out of business when he promised him an unreleased song to be put in the paper as a flexi-disc. Branson ramped up the print run, expecting a land rush of sales, but Lennon didn’t deliver. That story reflects just one of the misfortunes that Branson did not let push him offtrack.

In 1970, the Student employed almost twenty people—all earning £20 per week. But by that time, Branson had identified another avenue to explore. He knew how important music was to the readers of the Student. He also saw that regular record shops didn’t discount music, so he ran an ad in the Student offering cheaper mail-order records. The response was huge and a business was born. Of course, he knew they needed a clever name, and Virgin was suggested because they were all novices at business. Virgin Mail-Order Records took in bags and bags of mail orders, but the boom didn’t last. In January 1971, the Union of Post Office Workers went on strike for six months.

That obstacle put Branson once again in survival mode . . . a state which seemed to stimulate his creativity. He saw an opportunity to sell music in an actual retail store. At that time, record stores were dull, formal areas owned by people who knew little about what was new or exciting. The first Virgin record shop, located on Oxford Street in London, created an environment where customers could hang out, talk, and hear new music. While Nik was running the record store on a daily basis, Branson discovered that he could save some money by selling records that were for export and therefore cheaper. The decision to sell those records caused him to spend a night in jail, and his mother had to bail him out of the pokey. He ended up having to pay a fine of £60,000. Branson had always been a worker of the angles—looking for shortcuts—but that night he vowed he would never do anything that would cause him to be jailed or embarrassed again.

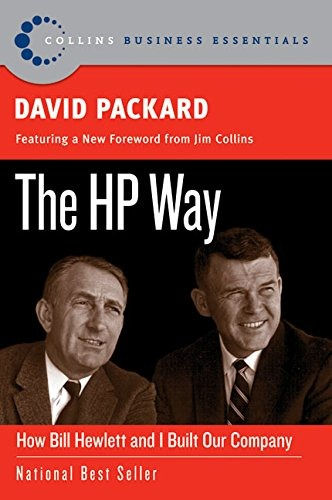

Hewlett-Packard may be notable to you for a variety of reasons. You might have an HP printer on your desk. Maybe you’re an avid fan of the history of the Silicon Valley and journeyed to the infamous garage where HP began. Perhaps you are intrigued by the rise and fall of Carly Fiorina, or maybe you watched the 2006 imbroglio involving leaks and finger-pointing in HP’s boardroom.

But maybe you also have heard of “the HP Way,” the management approach about which Jim Collins writes, “The point is not that every company should necessarily adopt the specifics of the HP Way, but that Hewlett and Packard exemplify the power of building a company based on a framework of principles.” Hewlett-Packard is an American success story, and The HP Way tells the story of how the company came to be and why its singular approach led to singular success.

Hewlett and Packard were unlikely partners. David Packard was born in 1912 and became an all-star basketball and track athlete. As a child he was very much interested in radio and electrical devices and later was accepted to Stanford to study electrical engineering. During his first fall at Stanford in 1930, he met Bill Hewlett, in many ways his opposite. Hewlett was dyslexic and struggled early in school. He was accepted to Stanford only because his father taught there. He joked that he chose electrical engineering because he liked electric trains.

While at Stanford, Hewlett and Packard became close friends. In 1937, they had their first “business” meeting to discuss starting a company together.

Packard would manage the manufacturing tasks for the company while Hewlett would focus on the circuit technology and engineering. Their partnership was formed in 1939 (the sequence of the surnames for the company name came from a coin flip). Their first product was an audio oscillator used to create steady audio frequencies. (They called it Model 200A because that number made it seem like they had been in business awhile.) Meanwhile Hewlett, a bachelor, moved into the one-car garage behind the house Packard rented with his wife. That garage, now a landmark considered “the birthplace of Silicon Valley,” became their first workshop.

By 1964, Hewlett-Packard had come a long way from its first product. The company’s total sales were $125 million, and all revenue came from scientific instruments. The two innovated further, developing an automatic controller that quickly found more sales as a minicomputer, not as an accessory, and that set the trajectory for their future business. The company continued to evolve, diversifying its products. Consider that in 1994, HP’s sales from computer products, service, and support were almost $20 billion, or about 78 percent of the total business.

The metal titanium was named after the Titans, a mythological race of powerful Greek men. If we gave crude oil such a namesake today, we would call it Rockefeller, after the first man to transform this natural resource’s power into a worldwide commodity and wealth-amassing enterprise. John D. Rockefeller set the standard (no pun intended) for big business, and it is his story that esteemed biographer Ron Chernow tells in Titan.

Rockefeller was in the right place at the right time to make history: Cleveland, Ohio, in 1853. Cleveland was home to one of five major refinery areas in America, and the young Rockefeller, having moved to Cleveland with his family during his teenage years, became an expert in converting petroleum into kerosene to be used for lighting. His career grew spectacularly in the early days because of hard work and his ability to cut costs and understand the big picture. Petroleum traveled on the railroads in barrels, and Rockefeller discovered he could make his own barrels cheaper than outsourcing them, thereby saving $150 per barrel: just one small example of his thrift. He also had the unusual advantage of being able to secure loans from local bankers because of his trustworthy Puritan upbringing and his smart business sense. By 1868—just five years after he began—his plants’ refining capacity was greater than the next three largest refineries combined. In 1870, Standard Oil was born.

Chernow makes it clear in his retelling that Rockefeller was aggressive in his desire to maximize profits and change the industry. In 1871, the head of the Pennsylvania Railroad proposed a consolidation of the fragmented refining industry that would have benefitted Rockefeller greatly. The plan was never implemented because when word leaked out about the estimated 100 percent increase in shipping charges—the profits from which would be shared by Standard Oil and the railroads—some refiners in the East protested. Things got violent in a Pennsylvania oil field, and after the upheaval, the railroads backed off and lowered their rates. Still, Rockefeller tried another approach and started to buy oil refineries and strengthen his hold on refining. He used aggressive tactics like selling below cost to show the other owners that they needed to sell before he put them out of business. In 1872, he bought up twenty-two of the twenty-six Cleveland competitors in a mere six weeks.

Ten years later, Rockefeller had multiple businesses in multiple states, which proved unwieldy to manage, and so the Standard Oil Trust was created to bring control to the diverse businesses. Despite the fact that the price of kerosene—the major commodity—dropped by 80 percent over the life of the company, the Trust had severe public relations issues because of Rockefeller’s aggressive business practices. These business practices were not illegal since there were no laws in place to rein in this kind of big business. As a result, less than a decade later, the government ordered the breakup of Standard Oil. Very few organizations have been combated by acts of Congress, but the Sherman Antitrust legislation was created in response to the Standard Oil Trust. Today, you need only to look at the growth of Wal-Mart and Microsoft as contemporary examples of companies struggling against bad public relations and accusations of acting as a monopoly.

5

2 Comments